The evolution of public transport in Spain

The demographic challenge to which the cities of Spain have had to adapt since the middle of the 19th century has generated an urban growth in the cities that still persists today. Urban dispersion has modified cities to the point of eliminating barriers that once existed, including the generation of new roads and transport nodes to meet the population’s demand for mobility.

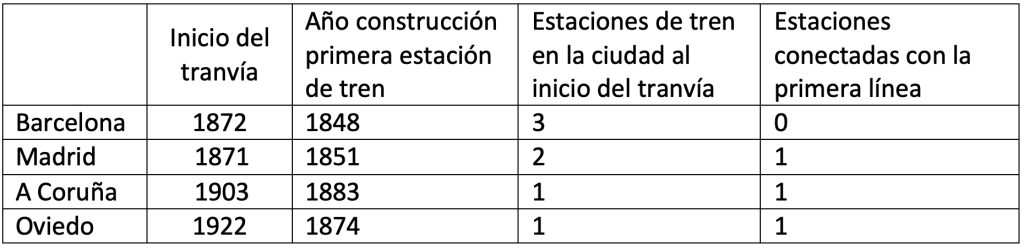

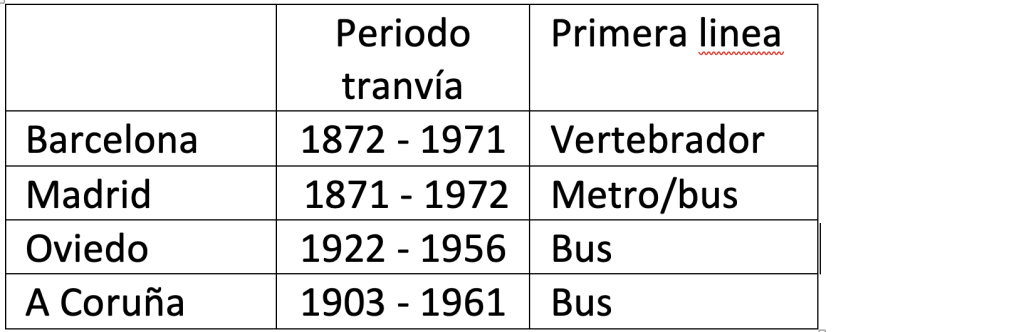

The purpose of this research is to make use of GIS methodology to analyze urban growth in four Spanish cities (Barcelona, Madrid, A Coruña and Oviedo) through cadastral information, and to compare this growth with the development of public transport in them. The common characteristic of these cities is to have had a public transport system based on the streetcar at some point in their history, which is why the analysis focuses on the development of this means of transport in the cities and on the historical period in which it was present, which mainly extended from the second half of the 19th century to the middle of the century.

The increase in population in many Spanish cities during the 19th century led to the need to create new urban spaces to accommodate the growing population. In response to this, architects and urban planners began to think about urban planning in a less immediate way, looking to the future and thinking not only about the need for new residential areas, but also for services that would improve the quality of life of citizens, such as transportation, water, sanitation, etc. infrastructure.

The emergence of the planned city concept has left a mark around the world, with impressive urban designs present on every continent. Notable examples include La Plata in Argentina, Palmanova in Italy and Canberra in Australia, each with unique characteristics that make them stand out in the world.

In urban planning, the nineteenth-century urban extensions constitute one of the nuclear milestones in the history of planning in Spain. One of the most relevant urban development plans in the country was known as the Cerdá Plan, created in 1860 by the engineer Ildefonso Cerdá with the main purpose of projecting the expansion of the city of Barcelona. This development followed the principles of the hypodynamic plan, an urban planning that orders cities with rectangular blocks and long, straight streets that are cut at right angles. The imprint of the Cerdá Plan in Spain caused this configuration to spread to other cities in the country, such as the widening of Cartagena, in Murcia, and Miranda del Ebro, in Burgos. That same year, Madrid’s widening plan was published, known as the Castro Plan, which took Puerta del Sol as its starting point and, like the Cerdá Plan, extended orthogonally, although with a notable zoning of the city, in which some industrial and residential land was already recognized. The 19th century also saw the development of the ensanches of numerous Spanish cities such as Valencia, Bilbao and San Sebastian, among others.

One of the novel elements in the urban society of the 19th century was the rise of animal-drawn vehicles (carriages, horse-drawn carriages, etc.). The urban design plans of the 19th century were not oblivious to this reality and took these vehicles into consideration when defining street widths, turning radii, traffic accumulation, etc. Thus, important decisions were made at the design level, such as the definition of chamfers in the blocks, the design of avenues that broke the grid with oblique layouts or the establishment of a minimum width of sidewalks to separate pedestrian and vehicular flows. These elements have survived to the present day, and make it possible to deal effectively with today’s vehicular traffic, which has different dynamic characteristics and a higher density. The effectiveness of the design decisions made back then has proven to be valid for the demands of today’s society, and it could therefore be said that the 19th century urban planners not only designed the city for that time, but also for the future. In this sense, it is fascinating to verify the effectiveness of some extensions erected in a certain era to serve as a physical support for urban life today.

The purpose of this research was to analyze the relationship between transportation and urban growth in Spain by defining and determining a series of parameters that can help characterize the service. For this purpose, the researchers used the open source software QGIS.

This study focused on various Spanish cities; therefore, the conclusions served to establish the main characteristics that define the layout of transport systems within the urban area, and were the starting point for evaluating possible future research to establish comparisons with the current situation and provide improvements for the future of mobility. These conclusions may also be of interest to the companies in charge of mobility and transport in cities and also to municipalities that are considering introducing these services.

In Spain, many cities have had streetcars throughout their history, some of the most important being Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, Seville, Bilbao, Malaga, Zaragoza, Murcia, Vigo, A Coruña, Gijón, Santander, Oviedo, among others.

Main Spanish cities to implement tramway service since the end of the 19th century.

Main Spanish cities to implement tramway service since the end of the 19th century.

Most streetcar networks were phased out in the 1960s and 1970s due to competition from the bus and the growing popularity of the automobile. Today, several cities have revived the streetcar as a sustainable and efficient means of urban transport. The study will focus on four cities with very diverse sizes and populations: #Madrid, #Barcelona, #ACoruña and #Oviedo.

Once the cities under study have been determined, the characterization of the sample is carried out, which, in this case, is divided into two parts. On the one hand, to characterize the urbanism of each city, the year of construction of the buildings according to the information of the land registry; as for the characterization of public transport, parameters such as the layout of the streetcar lines, the year of implementation of each of them, the location of the railroad stations and their year of construction are determined. Thanks to QGIS software, all these parameters are gathered in the same file, by cities, in order to be able to analyze the information.

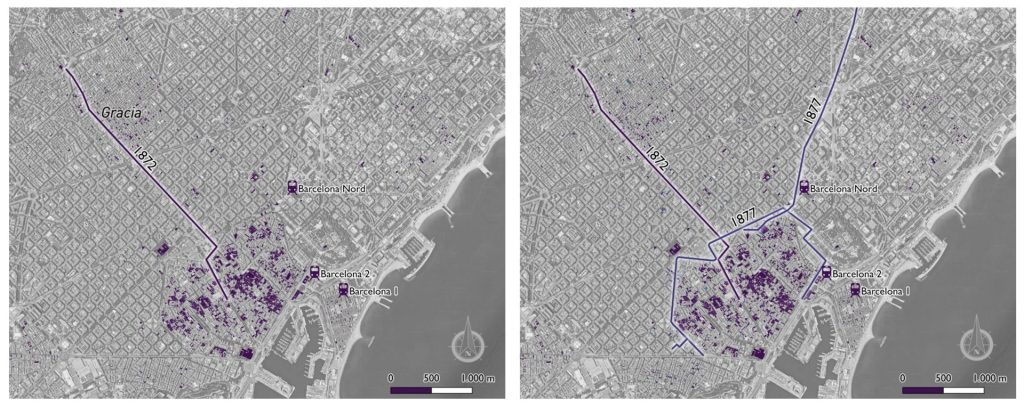

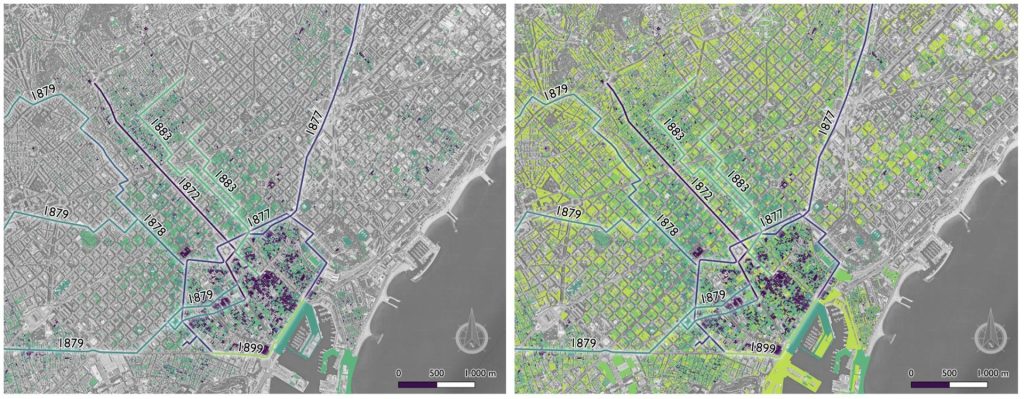

Barcelona

The first railroad station in Barcelona was called Barcelona I, located south of the city, on the outskirts of the wall. This station was built in 1848 and was also known as Mataró Station, as it was the head of the Barcelona – Mataró line. A few years later, in 1854, the Barcelona 2 station was built very close to Barcelona I, which ended up being known as Estación de Francia because it was the head of the line that was later extended to the border. In 1862 the Barcelona Nord station, also known as Tarragona Station, came into service. A few years later, the proximity of Barcelona 2 to the city center and the influx of passengers that it housed, made Barcelona I remained in the background and ended up being unified in the current Estación de Francia.

When the first tramway line in Barcelona entered service in 1872, there were three railroad stations in the city. However, the first route of this means of transport kept the c extended along the central sector of the city, taking into account the widening already planned by Cerdá, and seeking to connect the summer neighborhoods of Gracia, San Gervasio and Sarriá. Later on, the idea of creating a bypass tramway linking the city’s three railroad stations arose, and in 1877 the first section came into service, the same year in which the line linking the city with the Sant Andreu de Palomar neighborhood was inaugurated in order to improve mobility with the periphery.

The tramway network continued to expand, seeking a connection with the outskirts of the city, until 1899, when the perimeter of the ring road was closed, putting an end to tramway construction. Five years after the creation of the last section of the ring road, the tramway network defined the urban form of the city. In 1971, almost a century after the inauguration of the first line, the tramway network ceased to operate, although it was sufficient to have defined the urban stain of the city of Barcelona.

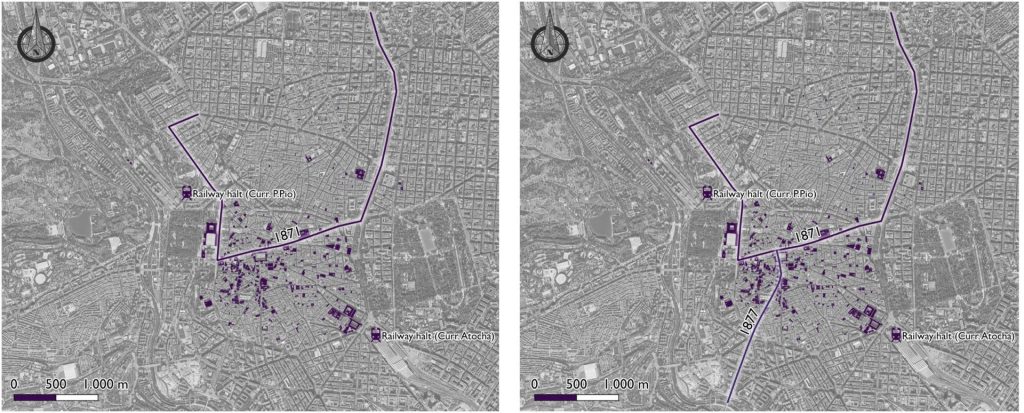

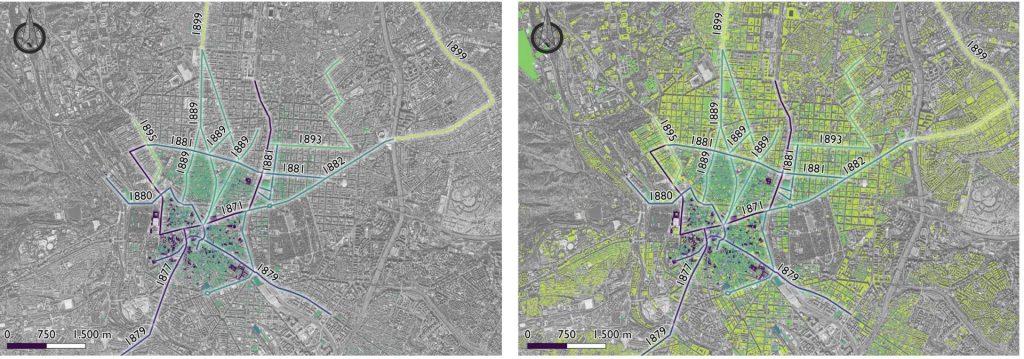

Madrid

In the year 1851, the first railroad service operated in Madrid, connecting the city with Aranjuez and, as a consequence, the first halt of the city was inaugurated in the same year: the Atocha halt (later Estación del Mediodía and current Estación de Atocha). The Atocha halt was originally a small train station, consisting of an elevated platform and a small booth for ticket sales. However, over time, the station was enlarged and modernized to accommodate the growing passenger traffic that transited through it.

In 1861 the Estación del Norte (now Príncipe Pío) was inaugurated, which began as a halt to serve the northern neighborhoods of Madrid and connect the city with other regions of Spain, although it was expanded due to the amount of traffic it carried.

The first tramway of Madrid started running in 1871, with a route that connected the Salamanca neighborhood with Las Pozas, passing through some places in the central area of the city such as Cibeles, Puerta del Sol and Bailén street. The objective of this line was none other than to connect the two districts of the city’s expansion with the city center. The second route was launched six years later, and in 1877 began the line linking the Plaza Mayor with the Toledo Bridge, seeking to improve connectivity with the south of the city.

In 1899 the last phase of the extension of the tramway network in Madrid began thanks to the well-known urban plan of the Ciudad Lineal de Madrid, the main objective of this project was to create an orderly city, with wide streets, gardens and green spaces, and an efficient transport system that could connect different areas of the city, highlighting the tramway as a backbone element.

Thus, between 1899 and 1904, a line began to operate that connected some localities of the city’s expansion area, such as Chamartín, Fuencarral, Pozuelo de Alarcón, Vallecas, Vicálvaro and Villaverde, with the city center (Comunidad de Madrid, 2021).

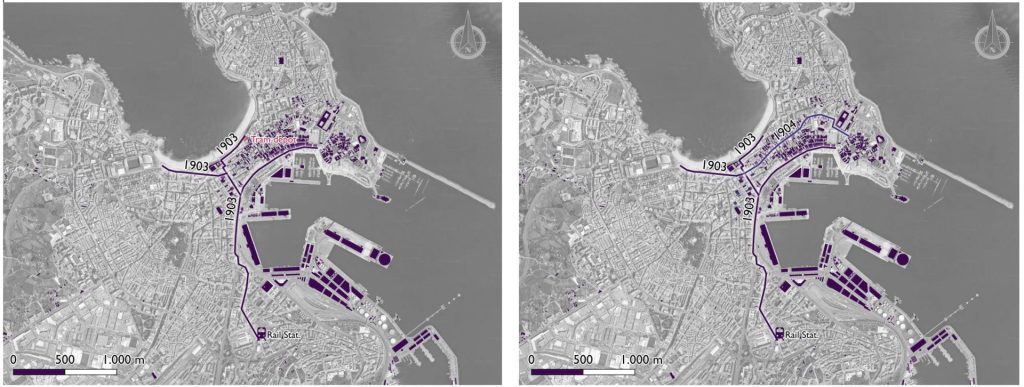

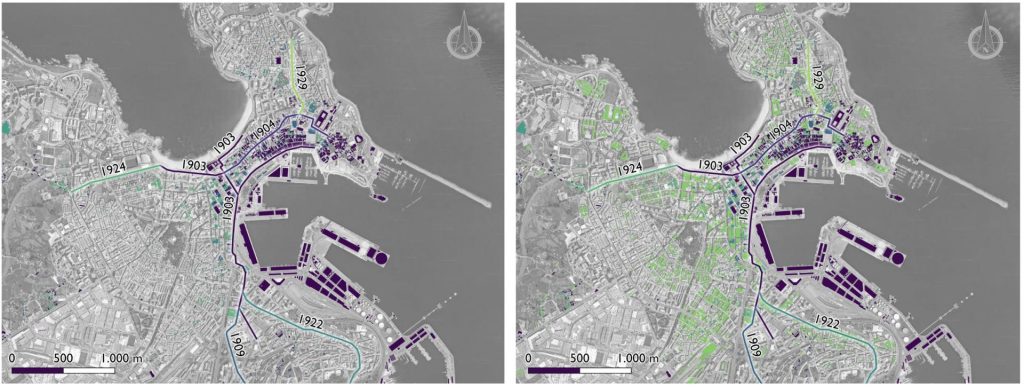

A Coruña

The train arrived in the city in 1883 with the station of La Coruña-Término, or Estación del Norte, which would connect A Coruña with Palencia.

The tramway arrived in La Coruña in 1903, when the first route connected Puerta Real, in the center of the city, with the train station, including two connecting branches to Riazor Beach and the tramway depot (Mirás-Araujo, 2005). The network grew, and in 1904 it was extended along San Andrés Street, the main road axis of the city, up to the area around the City Hall.

The tramway network continued to expand even beyond the urban area, until 1929, when the last extension of the network was inaugurated, connecting the center of the city with the vicinity of San Amaro beach. In 1961 this service ceased to operate in the city, although the period of operation was sufficient to define the urban growth up to that time, which followed the layout of the network.

The peculiarity of this mode of transport in A Coruña lies in its presence in the city throughout two different historical periods when it was recovered in 1997 as a transport icon in the city mainly for tourist purposes. In 2011, after a small derailment and finding flaws in the route, the streetcar was paralyzed again in the city.

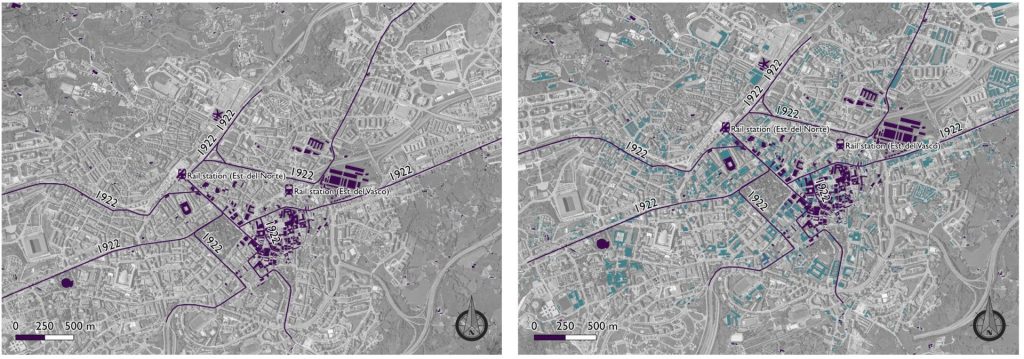

Oviedo

The appearance of public transport in Oviedo dates back to 1874, when the city’s train station (Estación del Norte) was inaugurated as the city’s transport hub on the Lena – Gijón railway line; later, in 1906, the Estación del Vasco was also inaugurated to connect the city with the railway line to Santander.

The tramway arrived in the city late, and in 1922 the four passenger streetcar lines that coexisted in Oviedo came into service (Plasencia-Lozano & Ruiz, 2021), all of them following a radial structure in the city and seeking the connection with the limits of the municipality to the north and south taking as a center the surroundings of the railroad station.

In 1956 the last tramway in the city circulated, although the 3 decades of service were enough to generate an urban growth that followed the route of the tramway lines.

Discussion and conclusions

The four cities analyzed already had railroad stations in the year the tramway was inaugurated, although they were used as connection nodes with other regions of the country. These stations were located on the outskirts of the city, so the tramway emerged as a solution to urban transport.

As for the layout of the first streetcar line in each city, the common factor linking all the lines is the search for a connection from the city center to the suburbs. However, the first line laid out in Madrid and Barcelona does not seem to focus so much on connecting the center with the railroad, but rather seeks the vertebration of the city. In the case of Oviedo and La Coruña, the first tramway line laid out in addition to structuring the city included direct connections with the railroad. This search for intermodality reached Barcelona with the creation of the second streetcar line, the circular line, which was created in order to skirt the urban area of the city while connecting the 3 stations present at that time.

In reference to the timing during the construction of the lines, there is also a clear difference according to the year of implementation of this type of transport: in Barcelona and Madrid, which were the first two cities to have a tramway, 7 years elapsed between the first line and the second. On the contrary, in cities with a late tramway system there are no significant time differences, and in La Coruña the second line came into service only one year after the first; in Oviedo, it did so the same year.

As for the configuration of the transport network once the construction of all the lines was completed, the radial configuration in all the cities stands out, offering lines that extended from the center to the suburbs and nearby towns.

Analyzing the operating time of the tramway systems in the cities, it has been detected that the smaller cities completed this service before the larger ones. Oviedo was the first city to end this service and Madrid the last. Smaller cities had more limited public transport systems and the number of inhabitants using this service was smaller; moreover, it was more economical and practical to replace streetcars with buses.

Regarding the growth of the urban area, certain limitations of the cadastral information have been detected, especially for buildings constructed during the 19th century. As it is a period so distant from technological systems and older information, it is less accurate; in line with this, in the 20th century there have been many modifications in the urban areas of the cities and, therefore, in the years of construction fixed in the cadastre.

However, despite these limitations, the information collected is sufficient to define the evolution of the cities analyzed and to represent the main conclusion, which is the relationship between urban planning and transportation.

During the initial years of the tramway service, the interaction between its layout and the growth of the city was not particularly evident. However, five years after the last line was put into operation, it can be seen that the urban sprawl of all the cities examined follows the course of the tramway network. In fact, the tramway route is sufficient to define the urban planning of the cities during the period of its operation, urban sprawl being a direct consequence of the deployment of the tramway network.

Study carried out by Irene Méndez Manjón, Traffic Engineer at Vectio, and Pedro Plasencia Lorenzo, professor at the Polytechnic School of Mieres, University of Oviedo.

Bibliography

Wheeler, S. M. (2003). The evolution of urban form in Portland and Toronto: Implications for sustainability planning. Local Environment, 8(3), 317-336.

Yanci, M. P. G. (2001). The impact of the railroad on the urban configuration of Madrid. 150 years of railroad history. In II Congreso de Historia Ferroviaria [Electronic resource]: Aranjuez, February 7-9, 2002 (p. 5). Fundación de los Ferrocarriles Españoles.

Mirás-Araujo, J. (2005). The Spanish tramway as a vehicle of urban configuration: La Coruña, 1903-1962. Revista de Historia del Transporte, 26(2), 20-37.

Reddy, R. L., Apoorva, B., Snigdha, S., & Spandana, K. (2013). GIS applications in land use and development of a city. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Adv. Eng, 3(5), 3-8.

Mondou, V. (2001). Daily mobility and adequacy of the urban transportation network a GIS application. Cybergeo: European Journal of Geography.

Álvarez-Palau, E. J., Martí-Henneberg, J., & Solanas-Jiménez, J. (2019). Urban growth and long-term transformations in Spanish cities since the mid-19th century: a methodology to determine changes in urban density. Sustainability, 11(24), 6948.

Brunn, S. D., Hays-Mitchell, M., & Zeigler, D. J. (2011). Cities of the world: global regional urban development. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Jefferson, C., & Skinner, J. (2005). The evolution of urban public transport. WIT Transactions on the built environment, 77.

Rodrigue, J. P. (2020). The geography of transportation systems. Routledge.

Ausubel, J., & Marchetti, C. (2001). The evolution of transport. Industrial Physicist, 7(2), 20-24.

Martinez, A. (2012). Energy innovation and transport: The electrification of trams in Spain, 1896-1935. Journal of Urban Technology, 19(3), 3-24.

Monclús, F. J., & Oyón, J. L. (1996). Transport and urban growth in Spain, mid 19th-late 20th century. Ciudad y Territorio estudios territoriales, 217-222.

González, R. A. (2015). The railroad in the city of Barcelona (1848-1992): network development and urban implications. Fundación de los Ferrocarriles Españoles.

Plasencia-lozano, p., & ruiz, r. (2021). The Oviedo electric tramway, an example of early 20th century urban infrastructure.

Goheen, P. G. (1993). The ritual of the streets in mid-19th-century Toronto. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 11(2), 127-145.

Velis, C. A., Wilson, D. C., & Cheeseman, C. R. (2009). 19th century London dust-yards: A case study in closed-loop resource efficiency. Waste management, 29(4), 1282-1290.

Bocquier, P., & Brée, S. (2018). A regional perspective on the economic determinants of urban transition in 19th-century France. Demographic Research, 38, 1535-1576.

Navas Ferrer, T. (2012). Urban growth, secondary network and electric tramway in the Barcelona area. In Globalization, innovation and construction of urban technical networks in America and Europe, 1890-1930 Brazilian Traction, Barcelona Traction and other financial and technical conglomerates (pp. 1-25). Edicions Universitat de Barcelona.

Muñoz de Pablo, M. J. (2011). Arturo Soria, ideologist and inventor of the Ciudad Lineal. Ilustración de Madrid, (19), 7-12.

Terán, F. D. (1968). La Ciudad Lineal, antecedent of a current urbanism.

Pérez Galdós, B. (2021). The novel in the streetcar.

Reyes Schade, E. (2017). Space and image of the streetcar in the articulation of the city. Módulo arquitectura CUC, 18(1), 135-146.

Main Spanish cities to implement tramway service since the end of the 19th century.

Main Spanish cities to implement tramway service since the end of the 19th century.